|

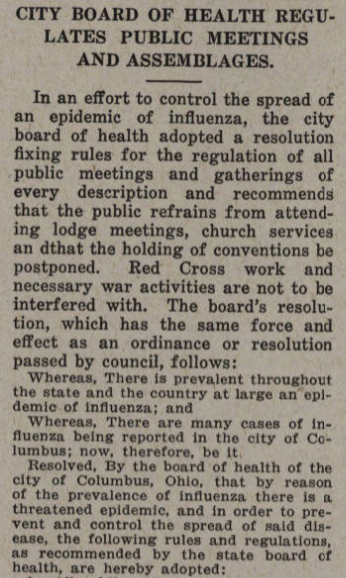

PART 1. "WE TURNED OUR FOOTSTEPS HOMEWARD" by Matt Doran From 1918 to 1920, an influenza pandemic swept across the globe, resulting in an estimated 50 million deaths. The United States experienced about 675,000 influenza-related deaths. The most deadly period of the pandemic came during the second wave in the fall of 1918.[1] By the end of the second wave in January 1919, nearly 15,000 deaths in Ohio were attributed to influenza, with about 1,000 in Columbus.[2] The Chronology of a Closure To slow the spread of influenza, many cities across the United States began cancelling public gatherings and closing schools in early October. Ohio cities including Dayton, Marion, Salem, and Sidney ordered schools closed by October 9.[3] In Franklin County, East Columbus (then a separate city from Columbus) closed after 42 cases of influenza among its students. County School Superintendent William S. Coy also reported closed schools in Canal Winchester, Groveport, Madison Township, and Reynoldsburg by this date.[4]

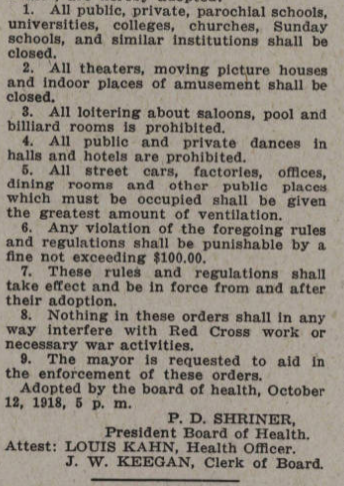

School resumed in January, 1919 as the second wave came to an end, and remained opened for the remainder of the school year. Month-by-month, influenza claimed the lives of 320 Columbus residents in October, 246 in November, 251 in December, and 67 in January. After only 76 deaths in February, a brief spike led to 165 deaths in March, followed by 57 in April, 42 in May, and 12 in June.[14] The Class of 1919 Remembers High school yearbooks from the class of 1919 offer a glimpse of student reactions to school closures. Writing in West High School's The Occident, senior class officer Helen Johnston noted:

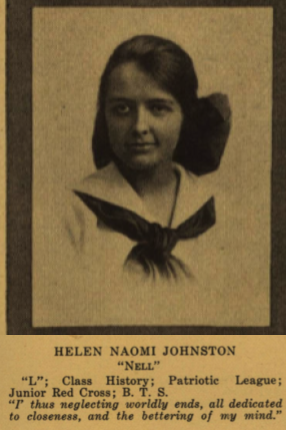

South High School’s "History of the Class of 1919" simply noted, “Interrupted by ‘flu’ vacations and independent vacations of our own we have managed to keep our studies and are being graduated with honor.”[17] North High School’s yearbook, The Polaris, celebrated the return of football season as classes resumed in November. On November 11, 1918 the Allies and Germany signed an armistice in France, ending the Great War. Meanwhile, on Ohio Field on the campus of the Ohio State University, North High School won 25-0 in a battle against Commerce High School. “After the ‘Flu’ epidemic had passed and the ban was lifted North and Commerce got together Monday morning, November 11, at Ohio Field. North’s squad showed needed pep and punch in carrying out plays. . . . Commerce put up a scrappy game on the defense, but when it came to team work on the offense, they were found sadly lacking in power. . . . The game was devoid of any thrills and showed lack of practice in both teams. . . ."[18] North High School football team from The Polaris yearbook, 1919 West High School also defeated South High School 20-0 on Ohio Field that day. The West yearbook summarized its season, “In-flu-enza and out-flew-football. With most of our out-of-town-dates cancelled because of the epidemic, the pigskin season settled into a race for local honors ....”[19] ENDNOTES

[1] Roser, Max. “The Spanish Flu (1918-20): The Global Impact of the Largest Influenza Pandemic in History.” Our World in Data. Global Change Data Lab, March 4, 2020. https://ourworldindata.org/spanish-flu-largest-influenza-pandemic-in-history [2] Kingseed, Wyatt. “From the Archives: Columbus Battles the Spanish Flu.” Columbus Monthly. March 30, 2020. https://www.columbusmonthly.com/news/20200330/from-archives-columbus-battles-spanish-flu [3] “Many County Schools Closed Because of Influenza Epidemic.” Columbus Evening Dispatch, October 9, 1918, 3. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.webproxy3.columbuslibrary.org/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1467499E363272B3%40EANX-163B4A53E61F7621%402421876-163B48DBCB14BDF3%402 [4] Ibid. [5] “Danger of Influenza Epidemic is Remote,” Columbus Evening Dispatch, October 8, 1918, 8. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.webproxy3.columbuslibrary.org/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1467499E363272B3%40EANX-163B4A530BAA27BB%402421875-1639EA9D4A9955BE%407 [6] Ibid. [7] “Influenza Encyclopedia.” Columbus, Ohio and the 1918-1919 Influenza Epidemic | The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918: A Digital Encyclopedia. University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine, n.d. https://www.influenzaarchive.org/cities/city-columbus.html [8] Bethea, Jesse. “‘Columbus Is Surrounded’ - When Spanish Flu Infected Ohio.” ColumbusUnderground.com, March 25, 2020. https://www.columbusunderground.com/columbus-is-surrounded-when-spanish-flu-infected-ohio-jb1 [9] Seifert, Myron T. “Columbus Public School System Has a Singular Heritage.” My History. Columbus Metropolitan Library, n.d. https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary.org/digital/collection/memory/id/23774/rec/197 [10] “Schools Closed for Second Time by Health Board,” Columbus Evening Dispatch, December 3, 1918. 2 https://infoweb-newsbank-com.webproxy3.columbuslibrary.org/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&t=pubname%3A1467499E363272B3%21Columbus%2BDispatch/year%3A1918%211918/mody%3A1203%21December%2B03&action=browse&format=image&docref=image/v2%3A1467499E363272B3%40EANX-163BA756A561FD86%402421931-163B4A275D321520%400 [11] Ibid. [12] Ibid. [13] Ibid. [14] Hooper, Osman Castle. History of the City of Columbus, Ohio. Memorial Publishing, 1920. 273. https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/WjWfaxIi7zgC?hl=en [15] West High School, The Occident, (Columbus, OH: 1919), 4, Columbus Metropolitan Library, https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary.org/digital/collection/yearbook/id/28396 [16] Ibid. [17] South High School, The Annual, (Columbus, OH, 1919), 28, Columbus Metropolitan Library, https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary.org/digital/collection/yearbook/id/4375 [18] North High School, The Polaris, (Columbus: OH, 1919), 89, Columbus Metropolitan Library, https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary.org/digital/collection/yearbook/id/18374/rec/19 [19] The Occident, 1919, 69 https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary.org/digital/collection/yearbook/id/28473

1 Comment

PART 2. HISTORICAL CONTEXT: INFLUENZA, WAR, AND PROGRESSIVE COLUMBUS by Matt Doran Columbus Schools and the War Effort Setting the 1918 influenza pandemic into the historical context of World War I and the Progressive Era sheds additional light on this event. The second wave of influenza in the fall of 1918 began during what turned out to be the final months of World War I. It was a period of heightened patriotism and sacrifice. The inconvenience of closures and cancellations surely paled in comparison to the greater sacrifices made for the public good, and indeed the threats to Americans’ civil liberties. To join the 2 million volunteers, the U.S. drafted 2.8 million men into military service[20], and prosecuted more than 2,000 dissenters for opposing the war or the draft.[21] The Espionage Act of 1917 made it a crime to interfere with the war effort or disrupt military recruitment. The Sedition Act of 1918 criminalized expression deemed disloyal. Many Columbus Schools alumni joined the fighting in World War I. Eddie Rickenbacker, who had attended East Main Street School, became America’s “Aces of Aces,” shooting down 26 German planes during the war. Chic Harley, a 1915 graduate of East High School, had already made a name for himself as a college football star at Ohio State when he became an army pilot in 1918. Harley came home from the war and played another season at Ohio State. But at least thirteen of his East High School schoolmates were among the fatalities of World War I.[22] South High School sent over 160 alumni to war and reported a loss of five soldiers, including one who died of influenza at Camp Sherman near Chillicothe. Over 100 West High School alumni joined the war effort as well, with just one loss of life.[23] On the home front, Americans supported the war effort by planting victory gardens and buying liberty bonds. Students also contributed to the war effort, including 9,000 children who joined the war garden army in Columbus.[24]

South High School’s "History of the Class of 1919" declared, “To prove our patriotism, instead of giving an elaborate party...money was used to purchase a Liberty Bond, to be left to the school as a parting gift.”[28] Because of its large German-American population, the need to demonstrate patriotism would have been especially acute for residents of the Southside. During the war, German books were burned at Broad and High Streets. German schools and the last German newspaper were closed and never reopened. Within a few blocks of South High School (then located on E. Deshler Avenue), Schiller Park was renamed Washington Park, Schiller Street was renamed Whittier, and Germania became Stewart Avenue. Columbus Schools in the Progressive Era The 1918 influenza pandemic came near the end of the Progressive Era, a period of social, political, and economic reforms. Expanding education was a primary goal of Progressivism. In 1910, only 48 percent of all students entering high school stayed beyond their first year, and only 7 percent graduated. [29]

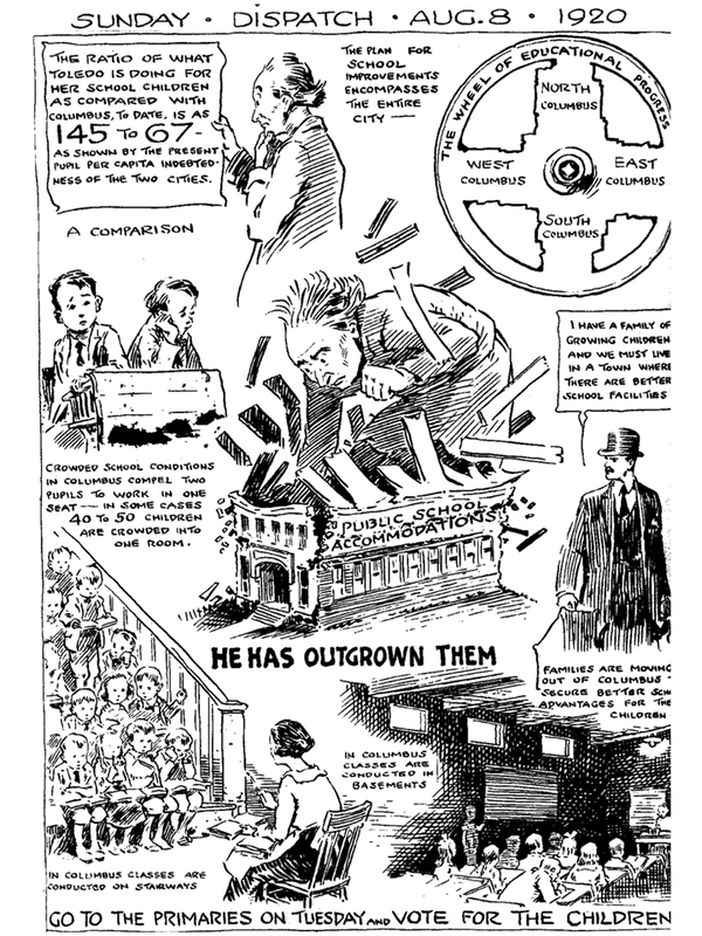

School lunch programs were present in at least some Columbus schools by 1918. In partnership with the Home and School Association, Columbus was one of the first cities to have an elementary school lunch program.[31] The first Penny Lunch program began in 1912 at Mound Street School. There was, however, no federally subsidized school lunch program in the United States until 1946. There are no records of school lunches being served during the influenza closures. The task of feeding the children almost certainly fell to families and local charities. Many families were already feeling the strain of the war. With men off to the army, women began assuming work outside the home on assembly lines producing trucks and munitions. The U.S. Food Administration under Herbert Hoover managed food distribution and prices, and led a campaign to teach Americans to economize their food budgets and grow victory gardens. Settlement houses were part of Progressive Era social reforms. Typically staffed by middle class women, these organizations were often located in immigrant neighborhoods of industrial cities. They provided education, healthcare, childcare, and social programs for children. Families in need may have turned to one of four settlement houses in Columbus in 1918: Godman Guild (1898), Southside Settlement House (1899), Gladden Community House (1905), and St. Paul’s Neighborhood House (1909). Founded by North High School English teacher Anna Keagle, the Godman Guild on W. Goodale Street served the Flytown neighborhood. As part of the war effort, the Godman Guild managed community gardens for 350 families in the spring of 1918.[32] The harvest surely helped families during the fall influenza pandemic. From 1908-1930s, free milk was distributed to families at the Godman Guild. With the end of World War I and the influenza pandemic, the United States experienced a postwar boom leading into the “Roaring Twenties.” Between 1910 and 1920, the population of Columbus increased from 181,511 to 237,031. By 1930, there were 290,564 Columbus residents.[33] To alleviate overcrowding in schools, Columbus built four new buildings for its high schools in the 1920s: East (1923), Central (1924) North (1924), South (1924), and West (1929). Three of the old high school buildings became jr. high schools. ENDNOTES [20] “Historical Timeline.” Selective Service System, n.d. https://www.sss.gov/history-and-records/timeline/

[21] Trickey, Erick. “When America's Most Prominent Socialist Was Jailed for Speaking Out Against World War I.” Smithsonian Magazine, June 15, 2018. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/fiery-socialist-challenged-nations-role-wwi-180969386/ [22] East High School, The Crucible, (Columbus, OH: 1921), 5, Columbus Metropolitan Library, https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary.org/digital/collection/yearbook/id/27704/rec/20 [23] The Occident, 1919, 8. https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary.org/digital/collection/yearbook/id/28412 [24] Hooper, 1920. 85. [25] The Occident, 1919, 4. https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary.org/digital/collection/yearbook/id/28396/rec/1 [26] East High School, The Crucible, (Columbus, OH: 1918), 81, Columbus Metropolitan Library, https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary.org/digital/collection/yearbook/id/27683/rec/11 [27] Ibid. 83 [28] South High School, The Annual, (Columbus, OH, 1919), 28, Columbus Metropolitan Library, https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary.org/digital/collection/yearbook/id/4374 [29] “Notable Milestones in the History of Columbus Public Schools.” Columbus City Schools, https://www.ccsoh.us/cms/lib/OH01913306/Centricity/Domain/158/CCS%20Through%20the%20Years.pdf [30] “School Development in the Last 27 Years.” Columbus School News, June 9, 1916. 5, https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary.org/digital/collection/yearbook/id/8957/rec/34 [31] Ibid, 8. https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary.org/digital/collection/yearbook/id/8962/rec/34 [32] Hooper, 1920. 85. [33] “Columbus Population,” World Population Review. https://worldpopulationreview.com/us-cities/columbus-population/ |

Archives

May 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed